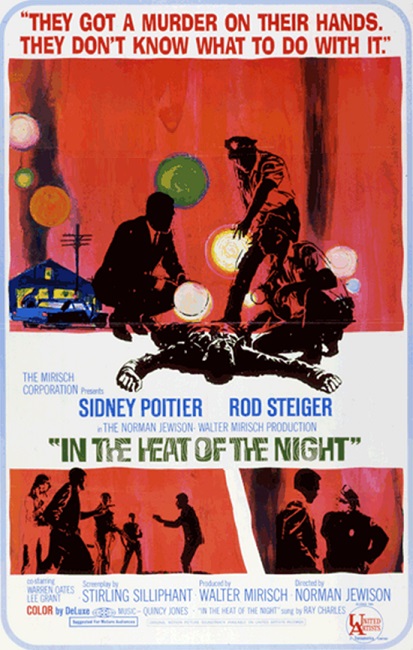

In the Heat of the Night – 1967

OK, it is time to come back down to reality. Over the last decade, starting with West Side Story, pretty much every Best Picture winner has been a break away from modern reality. What else did we have? Lawrence of Arabia, Tom Jones, My Fair Lady, The Sound of Music, and A Man For All Seasons. Period pieces and musicals. But In the Heat of the Night was different. This one took place in the 1960s, when the film was made and released. It was gritty and real and down to earth. It starred Sidney Poitier and Rod Steiger, who you may remember did a fantastic job in a supporting role in On the Waterfront.

Poitier was the biggest African American movie star at the time, having been in other hits such as Blackboard Jungle, Porgy and Bess, A Raisin in the Sun, Lillies of the Field, A Patch of Blue, and To Sir, With Love. This is significant because the Civil Rights movement was still in full swing. Martin Luther King Jr. was still giving speeches and the attitudes of many of Americans were changing for the better. And something very important happened in this film – something that was handled so appropriately that it had a major impact on the Civil Rights movement. It has been called the “Slap Heard Round the World.”

Here’s the set-up: Poitier plays Virgil Tibbs, an expert homicide detective from Philadelphia. He is visiting his mother in Mississippi and must wait for a train in Sparta. However, while he is waiting, a murder takes place in Sparta and he is arrested without even the benefit of being questioned. So, right from the very beginning, I began to understand that while this film was a murder mystery, it was even more a film about extreme prejudice in the South. Tibbs’ false arrest makes the attitudes of the southern police officers quite clear. To them, the color of the man’s skin determined his guilt. Fortunately, Police Chief Bill Gillespie has the brains to at least find out who he is before throwing him in a cell.

Upon learning that Tibbs is actually a very intelligent, well educated, and highly skilled homicide detective, he ends up recruiting him to help solve the murder. Several suspects are brought in and several conclusions are drawn. Gillespie and his men are ready to charge anyone who might even appear guilty and close the case. Tibbs, though, is a professional and is able to disprove the false accusations. Each time he does so, he puts on display the stupidity and prejudice of the white officers, proving that a black man can be smarter than they. For this, Gillespie tries to take any and every opportunity to get Tibbs to leave town, only to turn around and make him stay when he realizes that he needs him to solve the crime.

At one point in the investigation Gillespie and Tibbs must go to no less than a cotton plantation owned by a white racist who might have a motive to commit the murder. Here is where the audiences of 1967 must have gasped as their jaws dropped to the floor. After learning that he is being questioned as a suspect in the murder case by a black investigator, the plantation owner, Eric Endicot, played by Larry Gates, treats Tibbs like he treats all his black plantation cotton pickers. He slaps him across the face. But Tibbs is not one of his glorified slaves. Without hesitation, he slaps the white plantation owner back.

By today’s standards, this might not seem like a huge deal, but in 1967 it was pretty major. To have a black man strike a white man in retaliation to blatant racism was not just one actor smacking another actor, even though the character had clearly been provoked. It was a blow for any African American who was ever treated as less than any white man. It was a victory that was the first of its kind and was very relevant to the social climate of the nation.

Endicot’s shocked and horrified reaction was also very telling of some social attitudes of the day. He asked Gillespie if he saw what had happened, to which Gillespie replied that he had. “So, what are you going to do about it?” Steiger was perfect in his answer, saying, “I don’t know.” Then Endicot said something about how it wasn’t too long ago when he could have had Tibbs shot for what he had just done. Then after the two men left, Endicot nearly broke down in tears, not in shame for his behavior, but because he is seeing the end of his racist way of life.

Interesting note: There is actually some small dispute over how the slap made its way into the film, as it was not in the original book on which the film is based. Poitier says it was put into the film under his instance. However, researcher Mark Harris says that the slap was actually already in Stirling Silliphant’s original screenplay.

I also found it very profound that, after Gillespie and Tibbs leave the plantation, Tibbs is so angry that he is almost ready to accuse Endicot of the murder and wants time to obtain the evidence needed to bring the fat cat down with a vengeance. Again, Steiger’s portrayal of Gillespie’s reaction was priceless. He said something like, “Well, it seems you are just like us,” making Tibbs realize that prejudice is not just a white man’s affliction.

It was all pretty powerful stuff, and the murder mystery was cool to follow as well. Aside from the important social significance of the film, Steiger and Poitier turned in some great performances. In fact, Steiger won an Academy Award for Best Actor, and I think he really deserved it. His character believably transformed from an ignorant bigot to someone who at least respected a black man enough to consider him an equal, possibly even a friend. And what made it all the more believable was the fact that in the end, he wasn’t a head over heels convert. He was clearly still uncomfortable with his newly enlightened attitudes. But he was able to at least stretch beyond his comfort zones, actually shake Tibbs’ hand, and wish him well.

Poitier also did a great job. He seemed very at ease in front of the camera. His lines were delivered with a wonderful confidence and gravity that did a great job of pulling the audience into the story, making you experience his troubles along with him. I was offended for Tibbs by the blatant stupidity and phenomenal prejudice of Gillespie and his officers, which, I think, was the point.

Of course, as is usually the case, when a famous quote from a film is put into the context of the plot, it makes so much more of an impact. The famous line, “They call me MISTER Tibbs!” is actually a pretty profound statement. The white police Chief, Gillespie, is yelling at him, sarcastically saying, “What do they call you up there in Philadelphia, boy?” His response really emphasizes the word MISTER. In other words – I am your equal!

Interesting note: During the filming, Poitier refused to do any filming south of the Mason-Dixon Line, out of fear for his physical safety. Apparently, that’s how dangerous it was for African American’s in the South in the 60s. So the film was shot in Sparta Illinois. They only used the name of Sparta in the film because the name of the town appeared all over the filming locations. However, I found it interesting that there actually is a town of Sparta in Mississippi.

And finally, I have to give two thumbs up to director Norman Jewison for having the courage to make a film with such an anti-racist message in a very volatile time in our nation’s history. Well done, Norman! His movie had a powerful message along with a positive agenda which came across loud and clear. This was a very good movie, well deserving of the Best Picture Award.