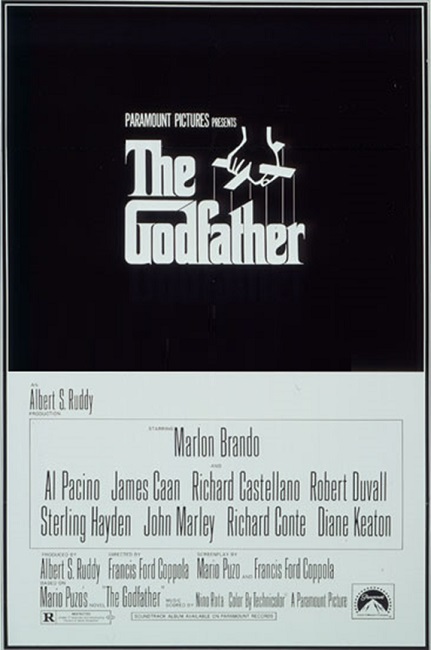

The Godfather – 1972

Everyone I have talked to about The Godfather has gone on and on, telling me how great the movie is. So, going into it, my expectations were high. Well, this time I was not disappointed. It really was an awesome film! Set from 1945 to 1955, this movie followed the lives of the fictional New York crime family, the Corleones. Director Francis Ford Coppola spearheaded this epic drama that spawned that famous line “I’m going to make him an offer he can’t refuse.”

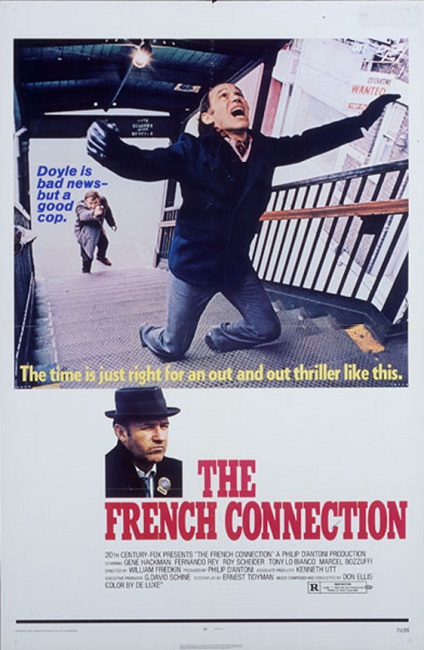

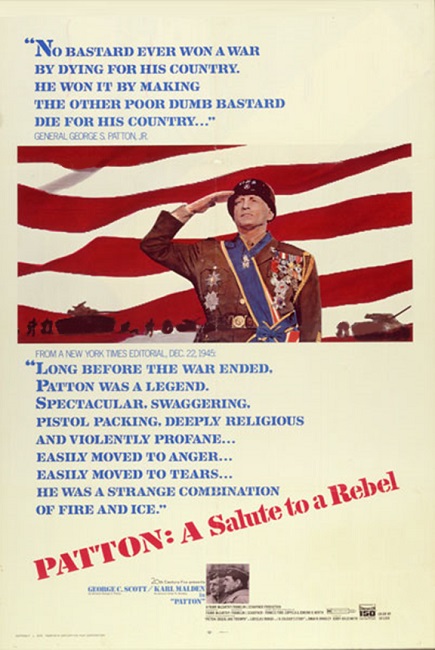

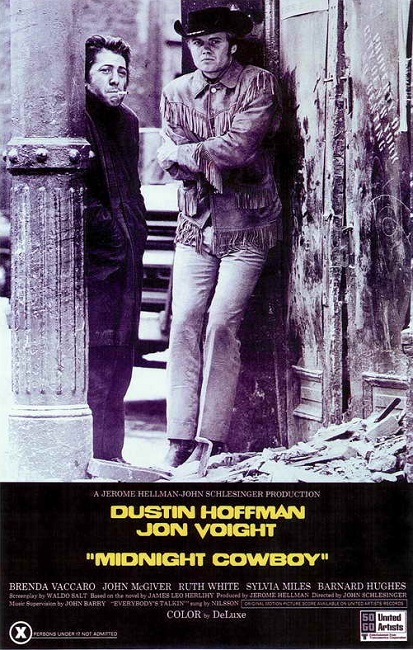

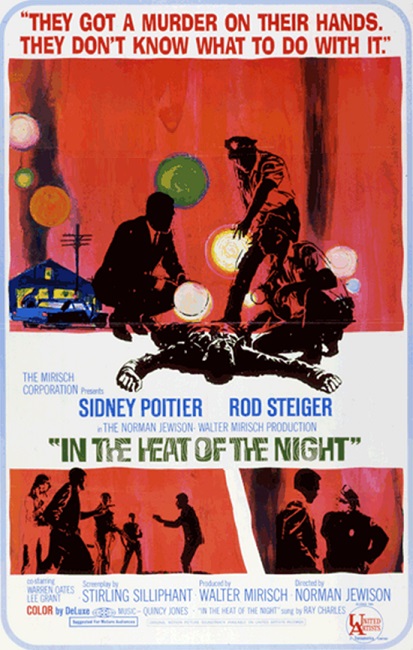

And epic is the right word. The plot was a big one on a grand scale. The music was wonderful, which was actually a noticeable relief. After some of the most recent movies like In the Heat of the Night, Midnight Cowboy, and The French Connection, which each had more pop or jazz scores, and Patton, which had an appropriate orchestral score, but was far too dispassionate and military for my tastes, The Godfather brings back a huge sweeping score, full of emotion, passion and individuality which I haven’t heard since Lawrence of Arabia in 1962. The score was written by Nino Rota. It sounded unmistakably Italian, reflecting the Italian roots of the Mafia family.

Every character was incredibly well written and believable. The casting was perfect and the acting was excellent. The sets and costumes were spot-on. The excessive violence was appropriate for the plot and never seemed gratuitous. The Godfather was almost a bit of a period piece, even for 1972, the setting being 27 years prior. The costumes and sets looked to be perfectly authentic. Even the cars had that circa 1945 look. Coppola really hit a home run with this one.

The film starts out at a wedding, during which Don (which means Boss) Vito Corleone, played by Marlon Brando, is conducting business. What this means is that people in his family or his community come to him to ask for favors that cannot be accomplished by any legal means. He commands their respect and even their adoration, and if he agrees to help them, they are indebted to him.

One such transaction, help asked of him by his godson, Johnny Fontane, in order to get a part in a film that he is being refused, is granted. Vito agrees to secure the part for him by putting pressure on the studio head Jack Woltz. He sends his consigliere (family lawyer) Tom Hagen, wonderfully played by Robert Duvall, to Woltz’s home. This is what leads to the famous horse head in the bed scene. You see, Woltz refused to cast Johnny in his movie, even after being asked to do so by Vito’s representative. After being refused, Hagen leaves politely. The next morning, Woltz wakes up to find the head of his prize stallion in his bed. OK, the severed horse head is scary enough, but to me, the most frightening part of the whole thing is that whoever decapitated the horse was able to get the head, which is no small item, into his bed WHILE HE WAS SLEEPING IN IT without waking him. The assassins were that stealthy. If they could do all that without even waking him, they could do anything they wanted to him, whenever they wanted to. Now, that is creepy!

Interesting note: Animal rights groups protested the use of a real horse head in the film. Coppola had to assure them that the horse’s head was delivered to him from a dog food company. No horses were harmed in the making of this film.

All that was to demonstrate how far Don Corleone was willing to go to accomplish his desires. Brando won the Academy Award for Best Actor for the role, even though he was not the first, second, or third choice to play the part. It is widely considered the best film role of his career. Once again, as in On the Waterfront, I have to acknowledge Brando as a fantastic actor. He truly did a great job.

Vito’s two sons were also great characters. His eldest boy, Sonny, is played by James Caan and his youngest son, Michael, is played by Al Pacino. They did a great job and were both, along with Robert Duvall (whose character was actually really cool) nominated for Best Supporting Actor for their respective roles.

Interesting note: Al Pacino boycotted the Academy awards that year, complaining that he was nominated for Best Supporting Actor instead of Best Actor, since he actually had more screen time than Marlon Brando. Brando actually refused his Oscar win and boycotted the ceremony in protest to the way American Indians were depicted in Hollywood and on television. Instead, he sent a Native American Indian in full Indian costume to the Awards Ceremony to explain his reasons for doing so.

I must admit that I have never been a huge James Caan fan, but I must concede that he was perfect for the role of Sonny. He was hot-headed and dangerous, and his death scene is pretty spectacular. It was also unexpected. I didn’t see it coming. Caan was very believable and earned my respect for the part.

But for me, the real star of the movie was Pacino. As Vito’s son, he is a part of the family and is aware of the criminal actions of his father. Yet he tries to maintain a distance from that side of the business. But after Vito survives an assassination attempt, Michael is beat by a corrupt police officer while protecting him from further harm. His response is to publicly murder the assassin and the Police officer, after which he is forced to leave the country. A large portion of the plot follows his transformation from the innocent young man to the dangerous head of the Italian Mafia, Don Corleone.

Pacino was also very young, and a fairly unknown actor at the time. He only had two movies under his belt, and even though producers thought him too short for the part, Coppola threatened to quit if Pacino was not cast. I thought he did a remarkable job. Back then, he had an innocent and youthful look that I’m sure appealed to audiences.

The story is fast-paced and action-packed with an ending that was very cool. I don’t want to give too much away, but after Vito’s death, Michael ends up taking over the family business, including the illegal parts. He does so with style, with brains, and with supreme vengeance. Even though he is a mafia boss, even though he lies to his wife Kay, played very well by Diane Keaton (who was so young I honestly didn’t even recognize her as the mature actress we all know today!), even though he orders a host of murders and is a dangerous criminal of the first degree, you end up rooting for him. He is a true antihero.

There are two fairly minor parts that I want to mention for their good acting. First was Richard S. Castellano, playing the part of Peter Clemenza, a hit-man for Don Corleone. He was also perfectly cast and did a great job. His level of devotion to Vito, and then to Michael was very well done. It sometimes seemed close to groveling, yet never over-the-top. Second was Simonetta Stefanelli, Michael’s first wife, Apollonia, whom he met while hiding out in Sicily. She was gorgeous and really looked her part. Her screen-time was brief but memorable.

The movie was incredibly popular with audiences. Its original budget was only 2 million, yet it made 81.5 million in its initial release, making it the highest grossing film of 1972. This was one of the big Best Picture winners, on par with Lawrence of Arabia, Ben-Hur, and Gone with the wind. It really deserved that coveted Best Picture Oscar!